From my Substack article: https://heronmichelle.substack.com/p/yule-old-gods-in-a-new-light

Old Gods in a New Light: A Modern Pagan Yule Rooted in Norse Tradition

posted Nov 15, 2025

Every year as the nights stretch to their farthest reach, witches and pagans gather to celebrate Yule—the winter solstice, the turning of the Great Wheel, and the sacred moment when the sun’s long descent into darkness finally stills, hangs at darkest ebb, then begins its ascent. For many modern witches, Yule imagery is a vibrant syncretic tapestry: a little Scandinavian Yule goat here, a sprinkle of Victorian Christmas warmth there, a sprig of Druidic Mistletoe, a dash of Wiccan “Reborn Sun God” mythos woven among evergreens, candles, holly berries, and hearth-fire blessings.

As eclectic as it may seem, this mix feels intuitively right. The winter holidays in the Northern Hemisphere have always been syncretic—layered folk customs stitched together across centuries. What we inherit is not a pristine ancient ritual but a dynamic, living tradition carrying perennial truths in seasonal symbolism.

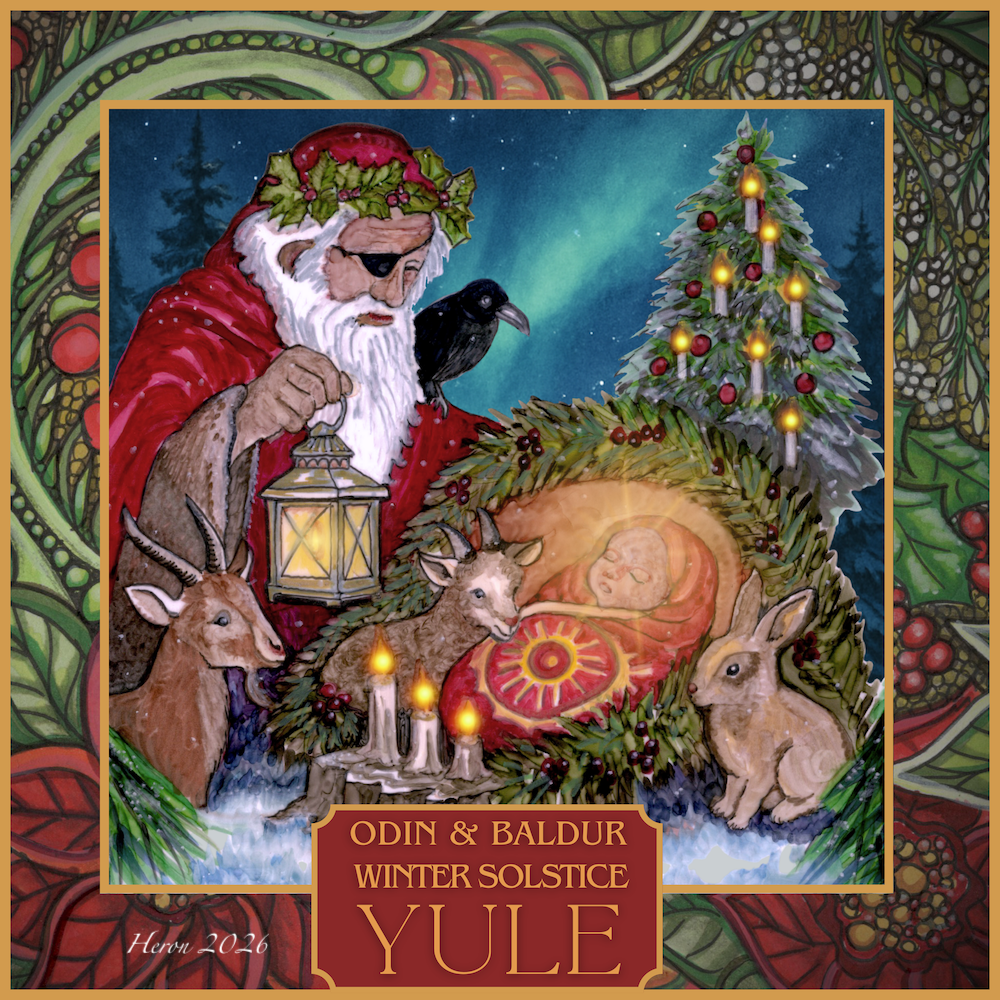

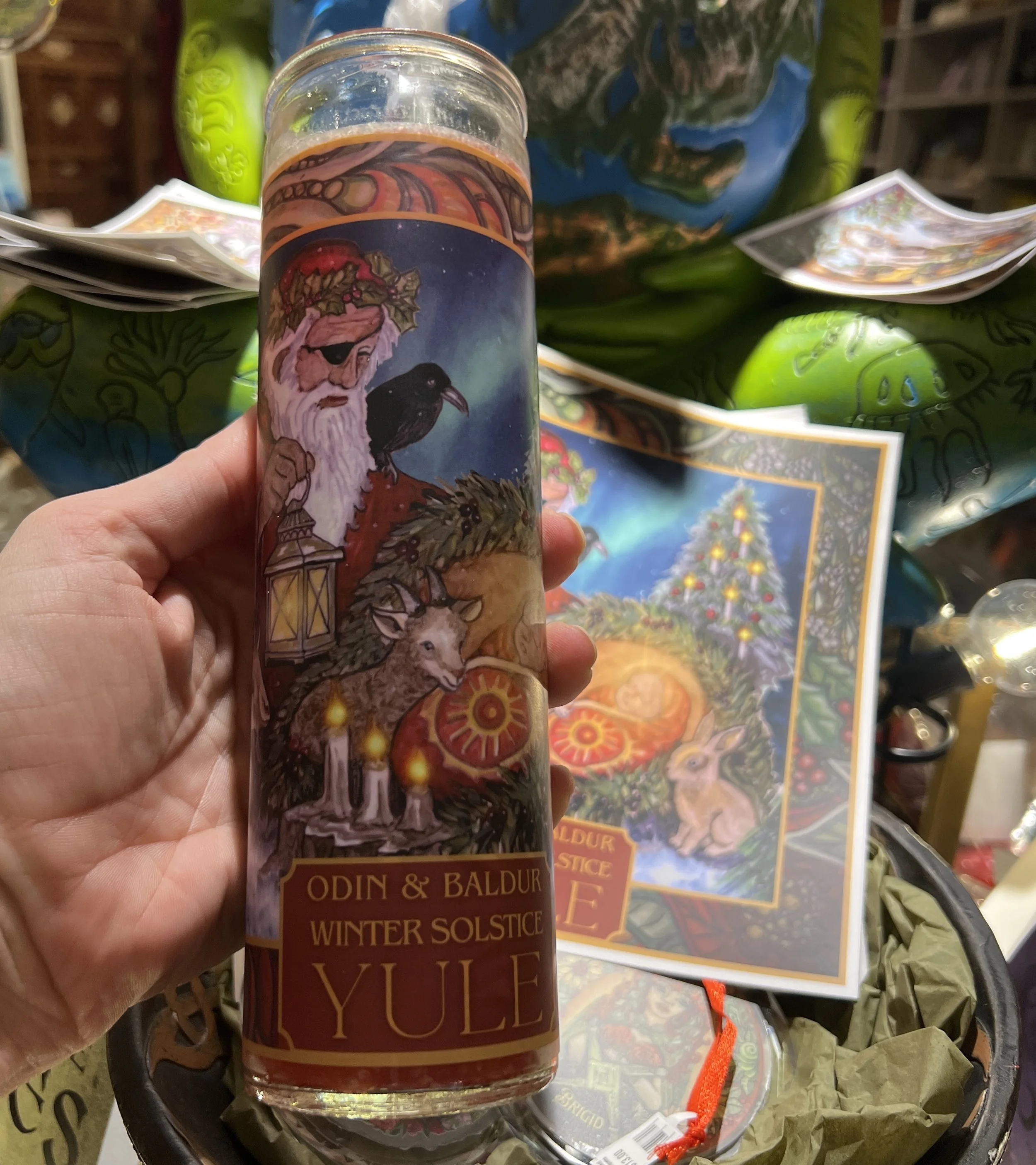

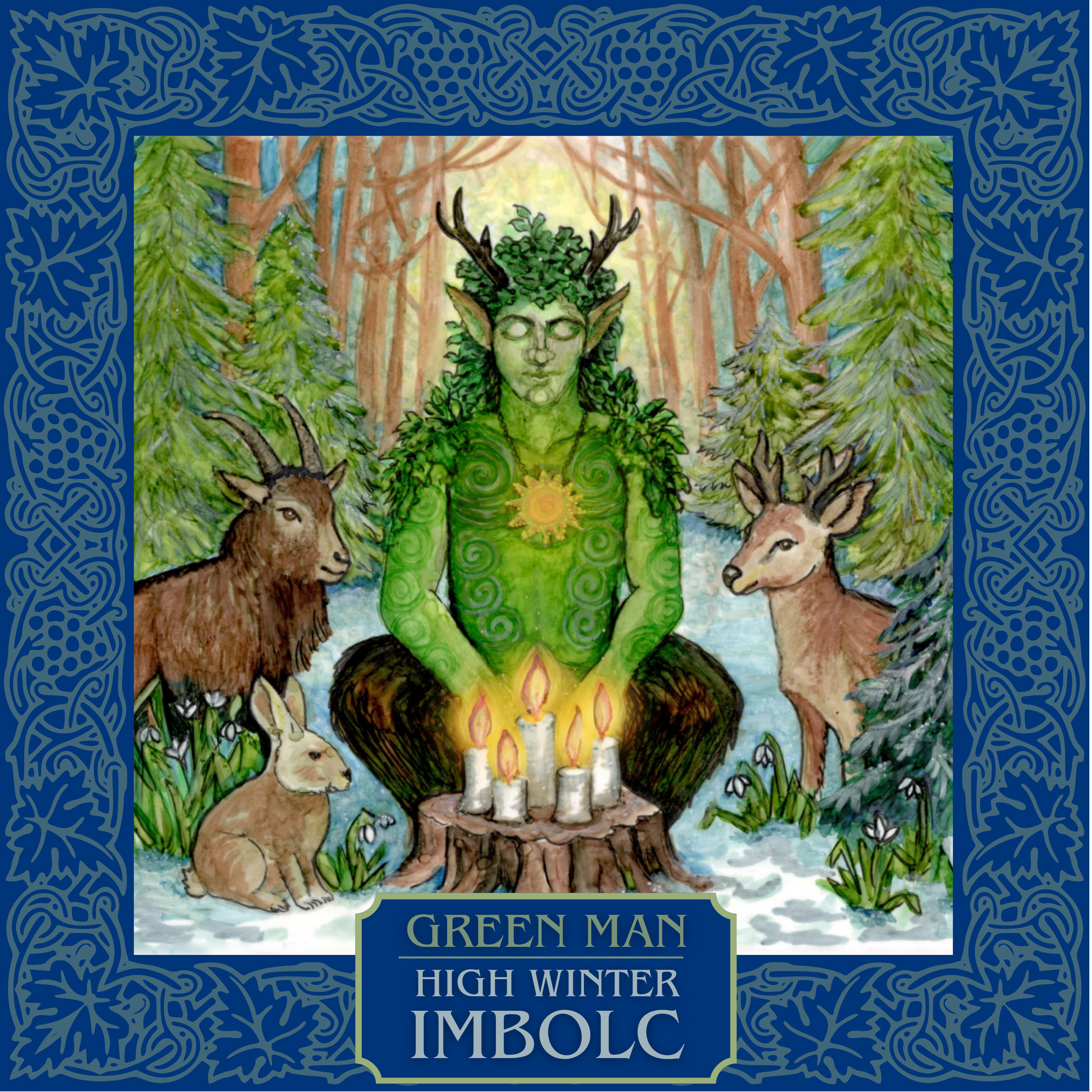

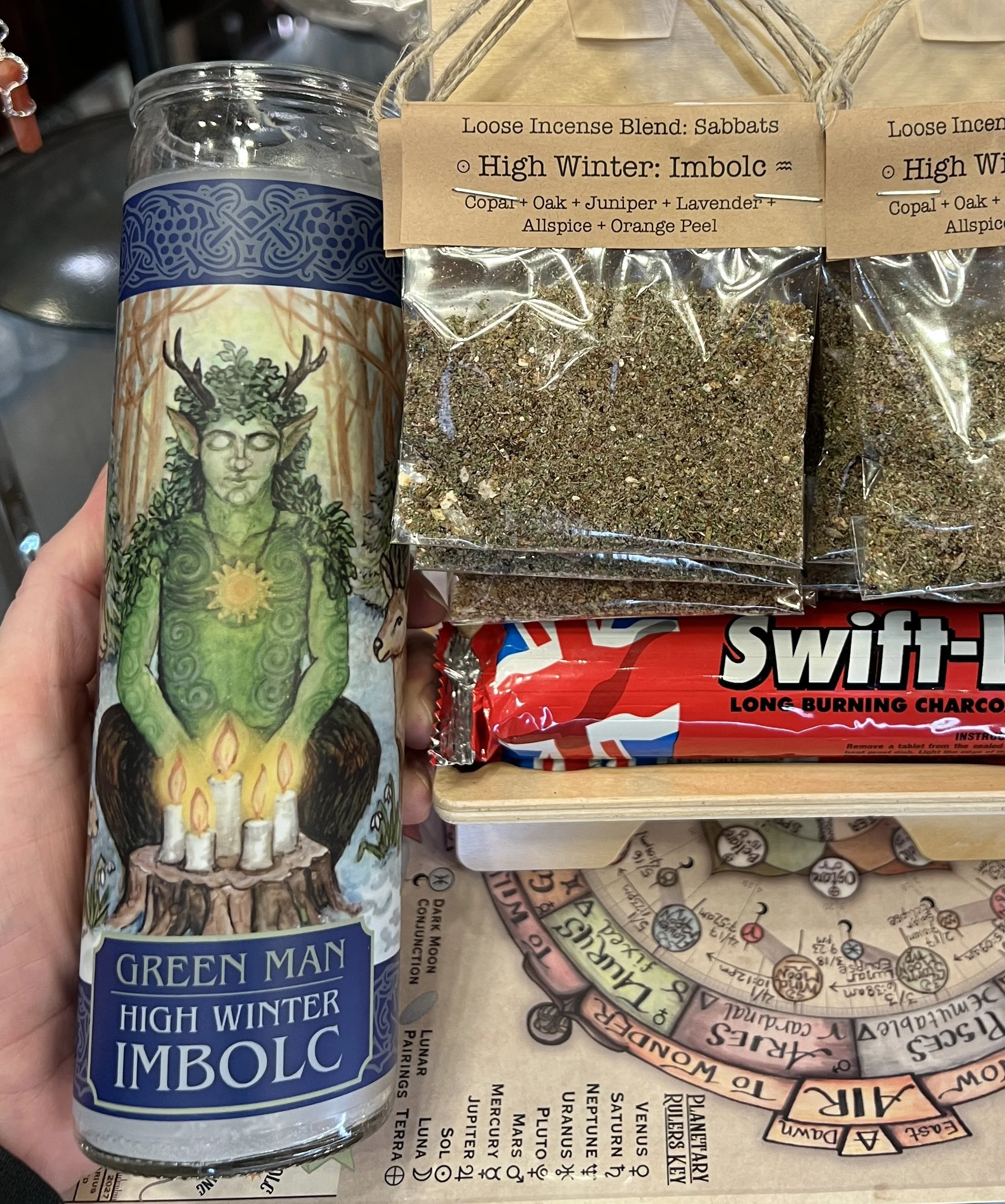

As I shift the focus of my magickal work on Solar Witchcraft—the third volume of the Pentacle Path series—I’ve felt called to dig into the mythic structure behind Yule. In Lunar Witchcraft, I appealed to specific cultural Goddesses for each lunar tide. Which specific gods from antiquity are the natural choice for reverence at the Sabbats? Especially if we are newly constructing a global Wheel of the Year. For decades I’ve been content to call upon the god at Yule in a vague “generic infant sun” motif. But I also see the Santa Claus and Holly King mythos relating to the Norse God Odin. So, how could we further incorporate the Norse and Scandinavian traditions from which Yule (Jól) historically arose? I would like to interpret these traditions through a modern pagan lens, the same way witches reinterpret lunar, elemental, and sabbat lore today.

Let me propose a model drawn from the old North and interpreted for the modern witch:

Odin as the Winter Elder (Sagittarius → Capricorn cusp)

and

Baldur as the returning Light (Capricorn’s newborn sun-current).

This is not reconstructionist heathenry, nor does it claim that Baldur was literally born at Yule. Instead, it is a mythopoetic syncretism—a respectful blending of ancient Jól traditions with the modern Wiccan Mystery of solar rebirth.

Jólablót: The Root of Yule

Our English “Yule” comes from Old Norse Jól, a midwinter festival involving sacrifice, feasting, ancestor veneration, and the renewal of luck (hamingja) for the coming year. (1) The winter darkness was not metaphorical—it was existential. Survival depended on community, the hearth, and the favor of gods and ancestors.

Odin himself bears seasonal titles associated with Yule: Jólnir (“Yule-One”) and Jolfaðr (“Yule-Father”). (2)

These epithets appear in medieval Icelandic sources and confirm his association with midwinter rites. Odin, roaming with the Wild Hunt through the black solstice nights, accompanied by ancestral or spirit hosts, presides over this liminal threshold where the old year dissolves.

In this sense, Odin embodies the Old God, the Elder of the waning year—the keeper of memory, magic, and fate as the light reaches its lowest ebb.

Baldur: The Light Lost and Returning

Meanwhile, Baldur is described in the Prose Edda as “the best and most beloved of the gods… so fair of face that a light shines from him.”^3^ He is the god of radiance, purity, hope, and harmony. His tragic death—brought about through Loki’s machinations—plunges the world into grief. Yet Baldur’s myth does not end in tragedy: he is prophesied to return after Ragnarök, ruling the renewed world. (4)

This makes Baldur an archetypal embodiment of: light lost, hope reborn, beauty restored, the world renewed after catastrophe. From a mythopoetic standpoint, Baldur resonates with the return of the sun after the longest night. Not literally a “sun baby,” but a symbolic expression of the returning brightness.

Modern witches, following a century of Wiccan tradition, celebrate the birth of the God at Yule as a seasonal Mystery—an archetypal truth that echoes Baldur’s narrative structure even if not his literal myth. This is my respectful syncretism.

Divine Dyad: Odin and Baldur as Seasonal Polarity

In Solar Witchcraft, I frame Yule as a two-fold god mystery that echoes the astrological movement from Sagittarius (mutable fire) into Capricorn (cardinal earth):

Odin — the Elder (Sagittarius)

Baldur — the Returning Light (Capricorn)

Odin, as Jólnir, presides over the death of the old year, guiding the Wild Hunt—much like the Sagittarius archer shooting the final flaming arrow of the cycle. He is the Winter Elder, a kind of “Holly King,” the wandering spirit-father navigating the deep dark.

Then, at the solstice dawn, a new light stirs. In modern pagan terms, we envision the returning sun as a newborn brightness—an infant wrapped in solar colors, held in a cradle of evergreen, protected by the animals of the winter forest. I’d imagine the baby goat of Capricorn snuggling into that cradle, keeping the new babe warm.

This image is not found explicitly in the Eddas, but it echoes the symbolic return of Baldur and the rebirth of the world after darkness.

Just as my new system of Lunar Witchcraft pairs deities across pantheons based on symbolic and magical function, Solar Witchcraft can likewise adopt Odin/Baldur as a seasonal axis without asserting historical claims.

Holly King as Folklore

This two-part model also resonates with broader European winter symbolism—especially the well-known Holly King / Oak King motif that many witches inherited from mid-20th-century Pagan literature. Although once commonly believed to be ancient Celtic lore, this seasonal battle between the twin kings is a modern mythopoetic construction, not a documented pre-Christian practice.

The earliest influential source for this idea appears in Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, where he proposed a universal pattern of “dying and resurrected vegetable gods” battling seasonally. (5) Frazer’s work was more comparative speculation than anthropological fact—but it profoundly shaped modern understandings of European folk motifs. His interpretation of seasonal kings was evocative, poetic, and compelling, even while later scholarship critiqued its lack of historical evidence.

The motif was expanded even further by Robert Graves in The White Goddess (1948), which presented a romanticized vision of ancient Celtic religion filtered through Graves’s poetic intuition, trance-like inspiration, and selective etymology. (6) Graves explicitly framed myth as poetic revelation rather than academically verified history. Many modern pagans later realized that Graves’s work—while visionary—should not be treated as literal pre-Christian lore.

Nevertheless, these texts dramatically influenced early Wicca. Gerald Gardner and later authors adopted the Oak King / Holly King cycle as a symbolic representation of the waxing and waning year. By the 1970s, the motif became widespread in Pagan liturgy, often presented (mistakenly) as ancient fact rather than modern mythopoesis.

Today, contemporary witches often express discomfort with earlier assertions that this motif was “ancient Celtic religion.” Thanks to improved scholarship in Celtic studies and folklore, we now understand it as a modern sacred story, not an archaeological one.

But that does not diminish its spiritual power.

Folklorist Alan Dundes famously defined folklore as “the traditional knowledge of a group, constantly re-created.” (7) The Oak King and Holly King represent a vibrant, evolving myth—a story sparked into being by 20th-century authors who—intentionally or not—served as channels for the seasonal gods re-emerging into contemporary devotion.

When viewed this way, Odin wearing the mantle of the Holly King becomes a symbolic mask—a poetic role in the winter drama that aligns with his attributes as a wandering winter father, psychopomp, and keeper of ancestral magic. Likewise, the Oak King, reborn at the waxing half of the year, can be reflected in the radiant imagery of Baldur or the archetypal “Solar Child.”

If myth is understood not as a fossilized record but as a living current, then these seasonal kings are not “fake history.” They are true in the way poetry is true, in the way trance revelation is true, in the way the gods whisper their mysteries into the hands of artists, writers, and priestesses willing to listen.

From this vantage, the Oak/Holly pairing is a modern mythic revelation. And like all revelations, it deserves to be honored with transparency, nuance, and creative reverence.

A Living, Growing Yule Tradition

Modern Witchcraft is a living tradition—not a museum piece. We honor what is known from the historical, linguistic, and mythological record, but we also acknowledge the creative responsibility inherent in contemporary pagan religion.

By syncretically weaving Odin and Baldur into the Yule cycle—with clear scholarly transparency—we root our seasonal rites in both ancestral lore and modern magical experience.

References

Carolyne Larrington, The Poetic Edda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), introduction; see also Rudolf Simek, Dictionary of Northern Mythology (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1993), 215–217.

John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 240.

Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda, trans. Jesse Byock (London: Penguin Classics, 2005), 32.

Völuspástanza 62, in Larrington, The Poetic Edda, 9.

James George Frazer, The Golden Bough (London: Macmillan, 1922), chapter “The King of the Wood.”

Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (London: Faber & Faber, 1948).

Alan Dundes, Interpreting Folklore (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), 6.

Claude Lecouteux, Phantom Armies of the Night: The Wild Hunt and the Ghostly Processions of the Undead (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2011).